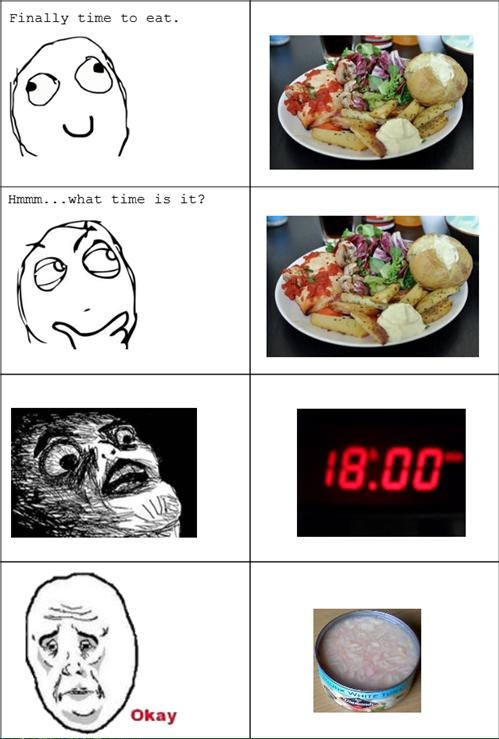

If late night eating interferes with fat loss, why do people who eat more in the evening lose more fat than people who don’t?

If carbs become fattening after 6 PM, how come people who eat more carbs after 6 PM lose more fat than those who eat them earlier in the day?

If we should “eat breakfast like a king, lunch a queen, dinner like a pauper”, then why does breakfast skipping and nightly feasts lead to fat loss and improved blood lipids?

If eating late is bad for you, why does almost every controlled study show that eating later in the day is better than eating earlier in the day?

And if the above statements are true, why do people still believe that late night eating is bad for you…?

The Late Night Eating Myth

It’s commonly believed that it’s better to eat more earlier in the day and less later in the day; eating late can supposedly interfere with fat loss and/or cause unwanted weight gain. In a nutshell, this myth is summed up by the saying that you should “eat breakfast like a king, lunch a queen, dinner like a pauper.”

You will often find proponents of broscience clinging to the notion that carbs somehow become more fattening after 6 P.M. This is nonsense of course.

You might already know that this is BS, as I debunked the late night eating myth in “Top Ten Fasting Myths Debunked” (Myth 10). In “Top Ten Fasting Myths Debunked” I concluded that there was no scientific evidence in support of the late night eating myth or the notion that we should eat more earlier in the day.

But the facts are actually more interesting than what I’ve previously stated; in controlled studies, late eating patterns are superior for fat loss and body composition.

In this article, I’ll review studies on temporal distribution of calorie intake and summarize the results. I will devote a bit of extra attention to the latest study, “Greater Weight Loss and Hormonal Changes After 6 Months Diet With Carbohydrates Eaten Mostly at Dinner”, which is what caused me to revisit this topic in the first place.

One pressing question first: Why is the late night eating myth still around if there are studies showing the exact opposite..?

Late Night Eating in Dietary Epidemiology

Someone asked this in comments:

Is it ok to eat dinner 1-2h before bedtime? Note that every damn meat eating mammal goes to sleep after consuming massive amounts of food e.g lions, dogs, bears but apparently somewhere down the line, nutritionist´s came up with the conclusion that we somehow evolved. So it would be nice if someone came with some evidence that you shouldn´t eat before bed. I really don’t understand why not, could you please explain?

Yes, how did nutritionists arrive at the conclusion that eating before bedtime is bad for you?

The late night eating myth is mainly another consequence of mistaking correlation for causation in dietary epidemiology. There are plenty of observational studies that have found a positive association between calories consumed in the evening and a higher BMI in the general population.

This association is solely attributed to the fact that Average Joe’s who like to eat more in the evening also consume more calories overall. In this study, it was deducted from food logs that late eaters consumed on average 248 calories more than the other group.

Similar relationships are commonly found in other observational studies on meal patterns. People who skip breakfast, skip meals and eat late at night are on average fatter and worse off than people who eat breakfast, regular meals and eat less in the evening. This has nothing to do with meal timing per se, but the lifestyle that goes in hand with “dysregulated” eating habits (as discussed in “Top Ten Fasting Myths Debunked”).

Meal pattern with omission of breakfast or breakfast and lunch was related to a clustering of less healthy lifestyle factors and food choice leading to a poorer nutrient intake.

(Ref.)

Late night eating is not only correlated to a higher calorie intake, but also less sleep time and more sedentary activities, i.e. watching TV and more time spent in front of the computer, which are additional confounders that can predispose people to weight gain.

Shift-Work and Circadian Rhythms

The imagined hazards of late night eating might also be the result of the scientific literature on shift-workers and metabolic health. Shift-workers are predisposed to a myriad of health disorders; obesity, poor mental health, cardiovascular disease, peptic ulcers and gastrointestinal problems (likely a result of chronic stress).

The negative effects of shift-work on health is mainly the result of a compromised diet, sleep deprivation, and stress – these tend to go hand. However, it’s possible that feeding under conditions of a disrupted circadian rhythm and an irregular meal pattern is an independent factor in the predisposition towards poor health amongst shift-workers.

Humans can adapt to a wide variety of feeding regimens depending on the habitual meal pattern. This entrainment takes place on a cellular level and is regulated by ghrelin, a hormone that increases during meal times and prepare your metabolism to best handle a nutrient load. Similarly, the circadian rhythm – when you awake and go to sleep – is regulated by daylight and habitual sleep/wake-cycle, and adapts your metabolism accordingly.

Simply put, your body expects a certain routine every day, depending on habitual diet patterns and sleep/wake cycles, and adjusts its hormonal profile and metabolism accordingly. If this pattern is haphazardly and constantly shifted back and forth, and never allowed to adapt, as is the case with many shift-workers – it’s very possible that it would be an independent factor in predisposing people to disease and health disorders. The hormonal profile of shift-workers tend to be less favorable than non-shift workers, for example.

It should be noted that permanent shift-workers, i.e. those who always work nights, or work nights on consecutive days, are better off than other shift workers, which is partly be explained by re-entraining the circadian rhythm; it seems that an “unpredictable” pattern, i.e. rotating day and night-shifts is the main culprit, as the circadian rhythm is constantly desynchronized. However, given the many confounders present amongst shift-workers, i.e. stress, sleep loss, calorie intake, it’s hard to isolate which factor does what, i.e. is feeding during biological night worse than sleep deprivation, etc.

Dietary Epidemiology vs Controlled Studies

The aforementioned studies are of no interest to us. We are interested in controlled studies, not dietary epidemiology and observations in the general population. If you use dietary epidemiology to tell people how they should be eating you get this: The USDA Dinner Plate. When you use controlled studies to draw a conclusion, you get something that looks a little bit more like this. Throw some veggies in there and you’re all set.

Controlled studies answers questions like “I’m on a 2000 calorie diet. How will fat loss be impacted if I eat most of those calories in the later part of the day versus the earlier part of the day?” That’s what interesting to us, so let’s look into this now.

Early Meal Patterns vs Late Meal Patterns: Controlled Studies

In all of these studies, calories were controlled and fixed for all groups. The only variable that differed was the temporal daily distribution of calorie intake. In late meal patterns, 67-100% of total daily caloric intake was eaten between 6 PM and bed time, and this was compared against an early meal pattern with an opposite pattern.

Starting with the earliest study and working myself down to the latest study, I’ll briefly summarize the results, comment on the validity of the study, and interject whatever else of interest I find in each study.

Note that I will not include studies on Ramadan fasting. In loosely controlled studies on Ramadan fasting, fat loss and improvements in health markers is commonly found. This is a paradoxical and interesting finding, simply for the fact that people eat in the middle of the night, shortly before bedtime, along with a concomitant increase in intake of sugary treats and baked goods (and sometimes total calorie intake). However, these are rarely calorie-controlled studies, i.e. participants do not have strict guidelines about what they should eat, which is why I will not include them in this review.

Study #1

Chronobiological aspects of weight loss in obesity: effects of different meal timing regimens.

Results: In the very first calorie-controlled study on meal timing from 1987, it was found that weight loss did not differ when participants ate their daily calorie intake in the morning (10 AM) or evening (6 PM).

While it’s interesting to note that lipid oxidation (fat burning) was consistently higher in the PM-group, the duration of the study (15 days) was very short, which makes it hard to draw any meaningful conclusion from it. Aside from lipid oxidation, there were no differences in cortisol levels, blood pressure or resting energy expenditure between the groups.

Study #2

The role of breakfast in the treatment of obesity: a randomized clinical trial.

Results: In this well-designed 12-week study, participants were habitual breakfast eaters and non-breakfast eaters, who were assigned a breakfast or non-breakfast diet. Interestingly, fat loss was greatest among ex-breakfast eaters who followed the breakfast skipping diet. This group ate lunch and supper and consumed 2/3 of their daily calorie intake at supper (6 PM or later).

In contrast, baseline breakfast skippers who were put on a breakfast diet got more favorable results than those who continued the breakfast skipping pattern. The implication of these seemingly paradoxical findings might be related to impulse-control; dysregulated eating habits, such as breakfast skipping, tend to go hand in hand with uninhibited and impulsive eating. Eating breakfast might therefore be of benefit for those with poor self-control, such as the ex-breakfast skippers in this study.

On the other hand, more favorable results were had with breakfast skipping amongst the “controlled” eaters (habitual breakfast eaters). This group would be more representative of us, meaning people who are used to count calories, follow an organized diet and not just mindlessly eat whatever is in front of us.

There were no differences between groups in regards to the weight loss composition (75% fat / 25% lean mass) or resting metabolic rate.

Interesting tidbit: The breakfast eating groups showed a slight increase in depression-induced eating whereas the subjects in the no-breakfast group showed a slight decrease. Furthermore, subjects in the breakfast group saw the diet as more restrictive than the no-breakfast group. Quote:

…the larger meal size of the no-breakfast group caused less disruption of the meal patterns and social life than did the smaller meal sizes in the breakfast condition.

Perhaps it was these favorable effects on their social life that also resulted in the no-breakfast groups showing superior compliance rates at the follow-up 6 months later (81% vs 60%).

Study #3

Results: In this study participants alternated between two 6-week phases of the same diet of which 70% of the daily caloric intake was eaten in the morning or evening respectively. Larger morning meals caused greater weight loss compared to evening meals, but the extra weight lost was in the form of muscle mass. Overall, the larger evening meals preserved muscle mass better and resulted in a greater loss in body fat percentage.

The greater weight loss associated with the AM [morning] pattern that we found in our study was due primarily to loss of fat-free mass, which averaged about 1 kg more for the AM pattern than for the PM pattern.

An interesting study with a few glaring limitations, mainly the small sample size (10 participants) and the way body composition was measured (total body electrical conductivity, which is somewhat similar to BIA discussed in “Intermittent Fasting for Weight Loss Preserves Muscle Mass?”).

This study also included weight training 3x/week, which was a serious confounder in this specific study design. Given that the PM-group consumed a greater percentage of their calorie intake post-workout, this study might simply show the benefits of nutrient timing, and not bigger PM meals per se.

AM-Setup

- Breakfast, 8-8.30 AM: 35% of total daily calorie intake

- Weight training (circuit style), 9-9.30 AM

- Lunch, 11-12 PM: 35%

- Dinner, 4.30-5 PM: 15%

- Evening snack, 8-8.30 PM: 15%

PM-Setup

- Breakfast, 8-8.30 AM: 15% of total daily calorie intake

- Weight training (circuit style), 9-9.30 AM

- Lunch, 11-12 PM: 15%

- Dinner, 4.30-5 PM: 35%

- Evening snack, 8-8.30 PM: 35%

As you can see, the PM-setup is quite similar to the “One Pre-Workout Meal” protocol of Leangains.

Finally, the researchers speculate on the muscle sparing effects of the PM-pattern:

Certain endocrine influences might have contributed to the difference in fat-free mass change between the meal patterns. Growth hormone secretion displays an endogenous rhythm that is partially linked with the sleep cycle. At night pulsatile secretion increases after 1-2 hours of sleep, with maximal secretion occurring during stages 3 and 4 of sleep.

Although the effect of prolonged changes in dietary intake or meal patterns on growth hormone release are not known, it is conceivable that a greater flux of dietary amino acids with the large evening meals, coupled with the known protein anabolic effect of growth hormone, might combine to favor deposition of lean tissue.

Study #4

Influence of meal time on salivary circadian cortisol rhythms and weight loss in obese women.

Results: Using almost the exact same setup as the aforementioned study by Sensi & Capani (1987), it was found that splitting the daily calorie intake evenly into five meals consumed every other hour between 9 AM-8 PM, eating all calories in the morning (9-11 AM), or in the evening (6-8 PM) did not affect weight loss, metabolic rate or cortisol differently. The limitations here are once again a very short study duration for each phase (18 days).

Quote for those worrying about cortisol and fasting:

At the end of the stages studied, we found no significant changes in the circadian rhythm of cortisol secretion regardless of the timing of diet ingestion, even after 22 h of fasting.

It might be worth noting that nitrogen loss, which is a rough marker for muscle loss, was not affected by eating time or meal frequency; there was no difference between the 5-meal phase or the 22-hour fasting phases with one AM/PM-meal.

Study #5

In this latest and well-designed 6-month study on calorie distribution throughout the day, participants who ate most of their daily carb-intake at dinner (8 PM or later) lost more fat, experienced greater fullness throughout the diet, and saw more favorable hormonal changes than those who ate their carbs earlier in the day.

Background: This study was founded on the premise that the diurnal peak in leptin can be altered, as noted during the month of Ramadan. (I’ve covered leptin and intermittent fasting here: “Intermittent Fasting, Set-Point and Leptin.”)

Previous studies have described a typical diurnal pattern of leptin secretion that falls during the day from 0800 to 1600 hours, reaching a nadir at 1300 hours and increases from 1600 with a zenith at 0100 hours. Ironically, this crucial hormone responsible for satiety is at its highest levels when individuals are sleeping.

It was hypothesized that consumption of carbohydrates mostly in the evening would modify the typical diurnal pattern of leptin secretion as observed in Muslim populations during Ramadan.

Simply put, the goal of this study was to see whether it was possible to shift leptin secretion to strategically induce greater satiety and diet adherence during the morning and noon of the next day, instead of having leptin peak during night time (as it does on a standard diet).

…it was predicted that the diet would lead to higher relative concentrations of leptin starting 6–8 h later i.e., in the morning and throughout the day. This may lead to enhanced satiety during daylight hours and improve dietary adherence.

Note that leptin displays significant latency in response to carbs; if you eat carbs before you go to sleep, you won’t be experiencing the peak until you wake up in the morning (an added bonus is that you sleep good with some carbs pre-bedtime).

This study also sought to examine the effect of the experimental diet on adiponectin.

Adiponectin is considered to be “the link between obesity, insulin resistance, and the metabolic syndrome”. Adiponectin plays a role in energy regulation as well as in lipid and carbohydrate metabolism, reducing serum glucose and lipids, improving insulin sensitivity and having an anti-inflammatory effect. Adiponectin’s diurnal secretion pattern has been described in obese individuals (particularly with abdominal obesity), as low throughout the day.

* Low adiponectin = bad. High adiponectin = good.

* When insulin is low, adiponectin is high, but adiponectin also follows a diurnal pattern; low during night time, high during daytime (in normal weight individuals).

…it was also hypothesized that adiponectin concentrations would increase throughout the day improving insulin resistance, diminishing symptoms of the metabolic syndrome and lowering inflammatory markers.

* In the obese, chronically high insulin causing chronically low adiponectin is a problem as it increases insulin resistance and inflammation. By omitting carbs during the earlier part of the day, the researcher’s hypothized that this would increase adiponectin and improve health markers more than the conventional diet.

Setup: Both groups received the same diet divided into breakfast, lunch, dinner and as three “snacks” (morning, afternoon, night):

- 1300-1500 kcal

- 45-50% carbs

- 30-35% fat

- 20% protein

Group A received the carbs evenly split throughout the meals and snacks. Group B received the great majority of the total carb allotment (~170 g) at dinner. There are no details concerning the exact macronutrient amounts provided at each meal but the full-text paper contains the menus of each respective group. I would estimate that approximately 100-120 g carbs were consumed at dinner in group B.

Results: Both groups lost weight and saw improvements on several health markers, but group B lost more weight (-11 kg vs -9 kg), body fat (-7% vs -5%), stayed fuller and more satiety, and improved their hormonal profile more than group A:

Hunger scores were lower and greater improvements in fasting glucose, average daily insulin concentrations, and homeostasis model assessment for insulin resistance (HOMAIR), T-cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, C-reactive protein (CRP), tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), and interleukin-6 (IL-6) levels were observed in comparison to controls.

As predicted, the big carb-rich dinner was able to alter leptin and adiponectin in a way that might have favored greater fullness and a better hormonal profile:

The experimental diet modified daily leptin and adiponectin concentrations compared to those observed at baseline and to a control diet. A simple dietary manipulation of carbohydrate distribution appears to have additional benefits when compared to a conventional weight loss diet in individuals suffering from obesity.

But what I found most interesting, at least for those of us who want to maintain low body fat, was that the carb-rich dinner increased average leptin levels compared to the standard diet:

Our experimental diet might manipulate daily leptin secretion, leading to higher relative concentrations throughout the day. We propose that this modification of hormone secretion helped participants experience greater satiety during waking hours, enhance diet maintenance over time and have better anthropometric outcomes.

Perhaps this is why me, and many others with me, have found Leangains/intermittent fasting to be such an easy way of staying lean once you’ve reached your goals.

This study was solid, but for some reason there was no mention of how body fat percentage was measured. Similarly, calorie intake was not set individually and according to energy needs. However, given that everyone had the same job (police officer), it’s fair to assume that physical activity did not vary much on an individual basis. Furthermore, sample size was very large (78 participants), which makes it unlikely that the results were confounded by these factors.

Summary

Dietary epidemiology commonly find associations between certain meal patterns and higher BMI / body fatness. However, this association can solely be attributed to lifestyle-related factors and eating behaviors; snacking in front of the TV in the evening, making poor food choices in general, and so forth. People who eat more in the evening simply eat more calories, which explains why they weigh more.

Calorie-controlled studies looking at the effects of distributing a fixed caloric load differently throughout the day are scarce; I have listed all of them above. These tell a much different story than the one found in dietary epidemiology. While short-term studies (15-18 days) do not find a statistically significant difference between early and late meal patterns, long-term studies (>12 weeks) show that late eating patterns produce superior results on fat loss, body composition and/or diet adherence. This might be explained by more favorable nutrient partitioning after meals due to hormonal modulation.

I understand that these facts might be hard to swallow for some people, given everything we’ve heard about late night eating being bad, fattening, and so forth. But then again, we hear a lot of strange things in the fitness and health community. Rarely do these old wives’ tales mix with reality; think of all the myths about fasting, alcohol and meal frequency, for example.

That’s all for tonight. I hope you’ve enjoyed the article and will rest easy knowing there’s nothing bad about late night eating and big meals before bedtime.